The spectacular photographs of China’s progress in creating artificial islands in the South China Sea have deservedly generated a flurry of attention in the media and punditry in the past week or so.

The pictures show the amazing transformation, over the past year or so, of submerged atolls into sizeable islands with harbours, roads, container depots, workers’ dormitories and even cement plants. The reclamation activities have been documented periodically since early 2014 by Vietnamese bloggers, the Philippines foreign ministry, defense publisher IHS Janes, and, most recently, the Washington-based CSIS’s Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative.

These images seem to have a special ability to catch people’s eyes and draw attention to the issue. On my own humble Twitter feed, where most posts are lucky to be noticed by anyone, when i’ve attached images of China’s artificial Spratlys, the stats suddenly light up with dozens of retweets, many from strangers.

With this viral quality, and visual impact, they could well become iconic images that define the South China Sea issue as a whole. So amidst the surge of interest, it’s worthwhile reflecting on what’s not in the pictures. Here’s my stocktake, together with a collection of less widely-circulated photos:

- The scoreboard: China is still well behind

- The company: reclamation is part of most claimants’ Spratly strategies

- The history: it’s not new, and that does matter for policy responses

- The regional context: easing tensions

- The environment: an unfolding tragedy

Additions, omissions and arguments most welcome!

1. The scoreboard: China is still behind

The photos show how the PRC’s construction and logistical prowess is enabling it to rapidly change “facts on the ground” in the disputed area. Significantly, however, it has not altered the occupation status of any feature, despite a very unfavourable status quo. Mainland China was the latest of latecomers to the Spratly scramble. Its rivals, Vietnam, the Philippines and Malaysia, all staked out islands and reefs by stationing troops there from the early 1970s onwards. Although the PRC regularly verbalized its claim from its founding in 1949, its ships only arrived in the late 1980s — and when they did, they had to win a live-fire battle with the Vietnamese Navy to establish their first tenuous foothold.

Today, China only occupies seven of the literally hundreds of reefs, shoals and islands of the archipelago. Vietnam has established permanent outposts on well over 20, and even the Philippines has more features under its control than China, with eight. Malaysia occupies another three. Right up to today, PRC personnel have never set foot on any of the dozen or so genuine islands in the Spratlys. So while the new photos quite rightly show that Team China is on a roll in the Spratly contest, they’re still well behind on the scoreboard.

Also less amenable to photography is the competition over the vast expanses of strategic maritime spaces. The waters surrounding the Spratly islands have bountiful fisheries and potential energy resources, and here the PRC’s position going forward is much stronger position than on the islands themselves. This is thanks to its large numbers of new Coastguard cutters, industrialized fishing fleet, and perhaps also its deepwater hydrocarbon drilling technology. On the other hand, all China’s rivals are upgrading their own capabilities, and all have permanent advantages in terms of geographical proximity. It is telling that the Philippines and Brunei have managed to carry out oil and gas operations in the disputed area despite having little capacity to secure them militarily, while the PRC so far has not.

Further to the west, safely distant from the treacherous shoals, lie the region’s main sea lanes. Carrying much of the trade, energy and raw materials that underpin most regional states’ economic development, this area is utterly vital to the CCP’s prospects of staying in power. This situation is a source of fundamental insecurity for the PRC since the security of this “lifeline” is ultimately guaranteed by the United States Navy (and even if the US were out of the picture, China’s weaker rivals could still threaten Chinese shipping with their submarines and other asymmetric capabilities).

Beyond the sea lanes, closer the coast of Indochina, geography tilts the playing field Vietnam’s way. We saw this last year when the PRC’s herculean HYSY-981 oil drilling platform required dozens of Coastguard and even PLA Navy ships to ward off harassment from rolling bands of Vietnamese fishing boats armed with little more than piles of driftwood. So again, while the PRC may have some momentum, it is still far from dominant in any of these maritime spaces.

2. The company: China’s rivals are reclaiming too

As AMTI’s Mira Rapp-Hooper noted at the end of her analysis, China’s rivals in the Spratly Islands have also engaged in extensive construction works over the years, including reclamation. Malaysia’s diving resort on Swallow Reef (my idea of a honeymoon destination, duly vetoed by someone more sensible), with its airstrip and reclaimed land, actually bears a superficial similarity to China’s at Fiery Cross Reef. By way of comparison, the Swallow Reef facilities take up around 0.35 sq km, which is only 1/3 of the size of the upgraded Fiery Cross. But it’s still around three times bigger than the PRC’s new islands at Gaven Reef 南薰礁, Johnson South Reef 赤瓜礁 and Hughes (often Kennan) Reef 东门礁, which are around 0.1 sq km. So China’s project may be bigger, but its scale isn’t out of the existing ballpark.

Much more sketchily documented are Vietnam’s land reclamation works in the Spratlys that were, as of May last year, proceeding at several locations in parallel with the PRC’s (see pictures below, and follow the link to the source to see more). I haven’t come across any updated pictures since then, but Taiwan’s defense ministry released surveillance information a couple of months agoreporting Vietnamese further military upgrades and reclamation at another island, Sand Cay 敦谦沙洲. In September 2014 a Taiwanese official told reporter Ralph Jennings high-res satellite imagery showed one of Vietnam’s landfill projects had already filled in an area equivalent to “eleven football fields”. A standard football field is about

0.01 0.007 sq km, so this too is roughly equivalent to the scale of the much better-known Chinese projects at Gaven, Johnson South and Hughes.

Top-bottom: Vietnamese works on Sin Cowe Island 景宏岛 & West Reef 西礁, May 2014, and Discovery Great Reef 大现礁 in 2013 (source: Thu Thiem)

Top-bottom: Vietnamese works on Sin Cowe Island 景宏岛 & West Reef 西礁, May 2014, and Discovery Great Reef 大现礁 in 2013 (source: Thu Thiem)

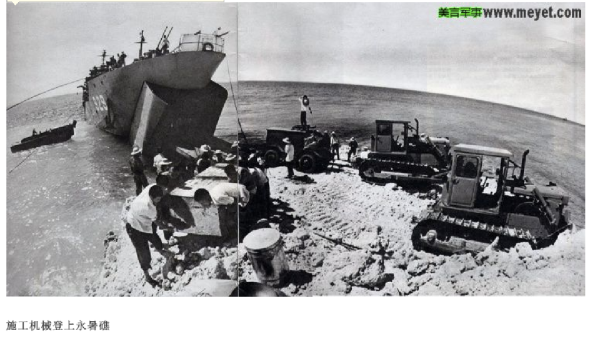

3. The history: it’s not a new approach (and that does matter)

Casual viewers of the recent dramatic photos might be forgiven for taking away an impression of a major PRC push towards asserting total control over the area. It certainly is an unprecedented effort to consolidate its position in the area. But in reality, engaging in unprecedented efforts to strengthen its position in the Spratlys is what China has been doing fairly constantly since the 1980s.

As i’ve mentioned here before, China upgraded its spartan “First Generation” outposts of the 1980s, known as huts-on-stilts 高脚室, to a “Second Generation” of pillboxes-on-stilts in the early 1990s. In 1995 it occupied an additional feature, Mischief Reef, and there, three years later, built its biggest structure yet (see pictures below). By the end of the 1990s “Third Generation” reef-castles 礁堡 with gun turrets and radars (and appropriately crenellated walls) were on each of the PRC-occupied reefs. Mischief Reef became home to an unprecedentedly large and well fortified structure that has served as a base for the PRC Fisheries Administration (including its law enforcement fleet) in the area. These were further expanded and upgraded in the 2000s, with helipads added to some.

Recognizing the continuities in China’s approach has potentially important implications for policy. Discussion continues to bubble, especially in Washington policy circles, over how the US and its allies should deter China from what some like to refer to as “bad behaviour”. Aside from abandoning such pompous terminology, the first task should be to understand on which kinds of actions a deterrence approach is most likely to work. A realist perspective might start by pointing out that assertive actions driven by insecurity, as opposed to expansionary ambition, won’t be easy to deter. However, it’s often hard to pinpoint the motivations of a particular action as either insecurity- or greed-driven, because in many cases it’s a mix. For example, to the extent that they might help China eventually control its own sea lanes, the reef reclamations could be seen as insecurity-driven. On the other hand, if they are used as bases for unilateral industrialized fishing and resource extraction, the Philippines and Vietnam would justifiably identify the motivation as greed. Then again, given China’s collapsing coastal fish stocks and ever-growing reliance on oil imports, one could also argue this too would be insecurity-driven.

Looking at the issue from the perspective of domestic politics might be helpful. The wheels of the Chinese Communist Party-state’s policymaking grind very slowly, and this suggests that long-established patterns of behaviour or carefully implemented consensus policies will be relatively difficult to deter. Upgrades to PLA facilities in the Spratlys, increasing routine Coastguard patrols, legal and administrative upgrades like the establishment of Sansha City and some other central aspects of what the CCP calls “comprehensive maritime management 综合海洋管理”, fall into this category. It would make sense, therefore, to concentrate on trying to deter more ad hoc PRC initiatives, rather than entrenched or regularized ones for which the wheels have been in motion for years or even decades. Examples of irregular or recent PRC initiatives include unilateral energy explorations in disputed waters, coercive on-water actions against foreign ships or fishing boats, and perhaps new ADIZ announcements. Refraining from these kinds of actions might require less of a reorientation of long-established policy or practice on the part of the PRC. And they are precisely the kinds of escalatory Chinese actions that the region as a whole has the greatest common interest in opposing.

4. The context: easing tensions

China’s new islands have drawn renewed international attention to the South China Sea issue, ironically at a time when China’s conduct has been relatively moderate for a while. Broadly speaking, it has not made any big moves in the South China Sea since July, when it withdrew the HYSY-981 from disputed waters a month ahead of schedule.

Since that time, Vietnam and China have held numerous high-level meetings involving Presidents,Defense Ministers, Foreign Ministers and other Politburo Standing Committee Members, each time addressing the maritime disputes and pledging cooperation. They also reportedly established a hotline between their respective fisheries authorities, promising to inform the other side within 48 hours of any detentions of the other side’s fishers. All the while, the reclamation work on both sides has apparently continued apace, suggesting they may have some kind of tacit or explicit understanding that both will be upgrading their outposts in the area.

The Communist Party’s Central Work Conference on Foreign Affairs last November indicated that Chairman Xi and the leadership might be planning on paying extra attention to relations with China’s “periphery” in the coming years. This is no reason to expect them to start backing down or altering basic policies in the disputed seas, but it does hold out the possibility that China could be more attuned to the strategic risks that destabilizing courses of action carry. The widespread, ASEAN-led expressions of “serious concerns” in response to China’s oil rig deployment in the Paracels last year may have helped Beijing realize the importance of not undermining regional stability if its “peaceful rise” is to be accepted in the long term. Similarly, Xi has shown signs of a new and more accepting attitude towards the premises of confidence-building measures with the United States, and there has even been some movement in this direction.

Unless we start to see escalatory countermeasures on the part of China’s rivals, it is not clear that the reclamation activities themselves are particularly destabilizing on either a regional or systemic level. To be sure, it would be better if they did not happen, but so far it appears that they are not the kind of action that demands an escalatory response from rivals.

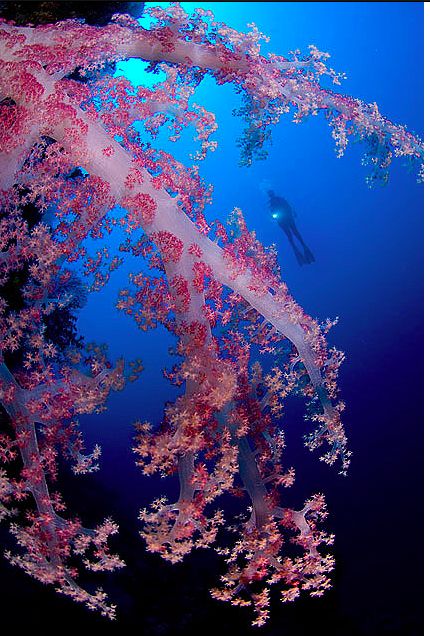

Spratly wonderland, Swallow Reef/Pulau Layang Layang (source: Layang-Layang Island, Malaysia Flickr group, users in file name)

5. The environment: an unfolding tragedy

Throughout discussions of the Spratly reclamation activities, the effects on this near-pristine natural environment have seldom rated a mention. In aerial shots, the dredged-up sand gleams white, and the harbour channels deep blue or brilliant turquoise, but the underwater wonderlands of the coral reefs — what is left of them — are merely shrinking areas of nondescript discolouration.

Until the 1970s the whole area was, by and large, conscientiously avoided by agents of the world’s states (with the notable exception of the Kingdom of Morac-Songhrati-Meads). Even today, the entire area is often marked on navigational charts as “DANGER AREA”, due to being pockmarked by treacherous reefs and shoals just below the surface of the water. But the disastrous effects of the sudden influx of human activity since the 1970s are already becoming apparent: a recent study by marine biologists found coral cover near Taiwan’s Itu Aba outpost declined by about three-quarters between 1980 and 2007.

The Chinese authorities are probably among the best-informed regarding the marine ecology of the Spratlys, having sent dozens of scientific missions to study them over the past 30 years. Perhaps the CCP has assessed the impact of these reclamation activities on the reef ecosystems; after all, it does at least seem keen to address the threat from destructive unregulated tourism in the Paracels. But it’s sadly apparent that none of the treasures of the Spratlys pictured above and below will be spared in the face of increased military, fishing and resource exploitation activities.

Spratly wonderland, Swallow Reef/Pulau Layang Layang (source: Layang-Layang Island, Malaysia Flickr group, users in file name)

None of this is to say China’s landfill activities aren’t significant, or that the latest batches of pictures are inaccurate or misleading. But the true significance of these activities isn’t yet clear. Carl Thayer says that the artificial islands would make useful fisheries and resource exploitation bases. Others believe it might be related to the Philippines UNCLOS case. Another theory is that the islands portend the announcement of a Chinese Air Defense Identification Zone over the South China Sea. This does make a lot of sense, given the runway taking shape at Fiery Cross Reef, though it doesn’t explain the upgrades at the other atolls.

It would also be a mistake to equate China putting the conditions in place to do so with an intention to actually make that announcement at the first available opportunity. In the recent past, notably in the case of Sansha City (and perhaps the East China Sea ADIZ), the PRC had everything in place many years before it eventually followed through. In the case of Sansha City, this careful, staged approach enabled China to squeeze every last drop of political juice from the initiative, wielding it for years as an eminently credible threat of punishment for its rivals. Patiently waiting for the right moment to follow through — in this case, the day that Vietnam enshrined its Spratly claims in a new domestic maritime law — allowed China to minimize the regional opprobrium associated with implementing a provocative, long-planned administrative upgrade. If there is a South China Sea ADIZ announcement coming, the timing, context and language could offer more valuable insight into the machinations and motivations of China’s policy in the South China Sea, and the meaning of its focus on “peripheral diplomacy”.

Nhận xét

Đăng nhận xét